Mandelson and Maude: The Unlikely Alliance That Took Butler to Task

Keir Starmer’s Civil Service Challenge

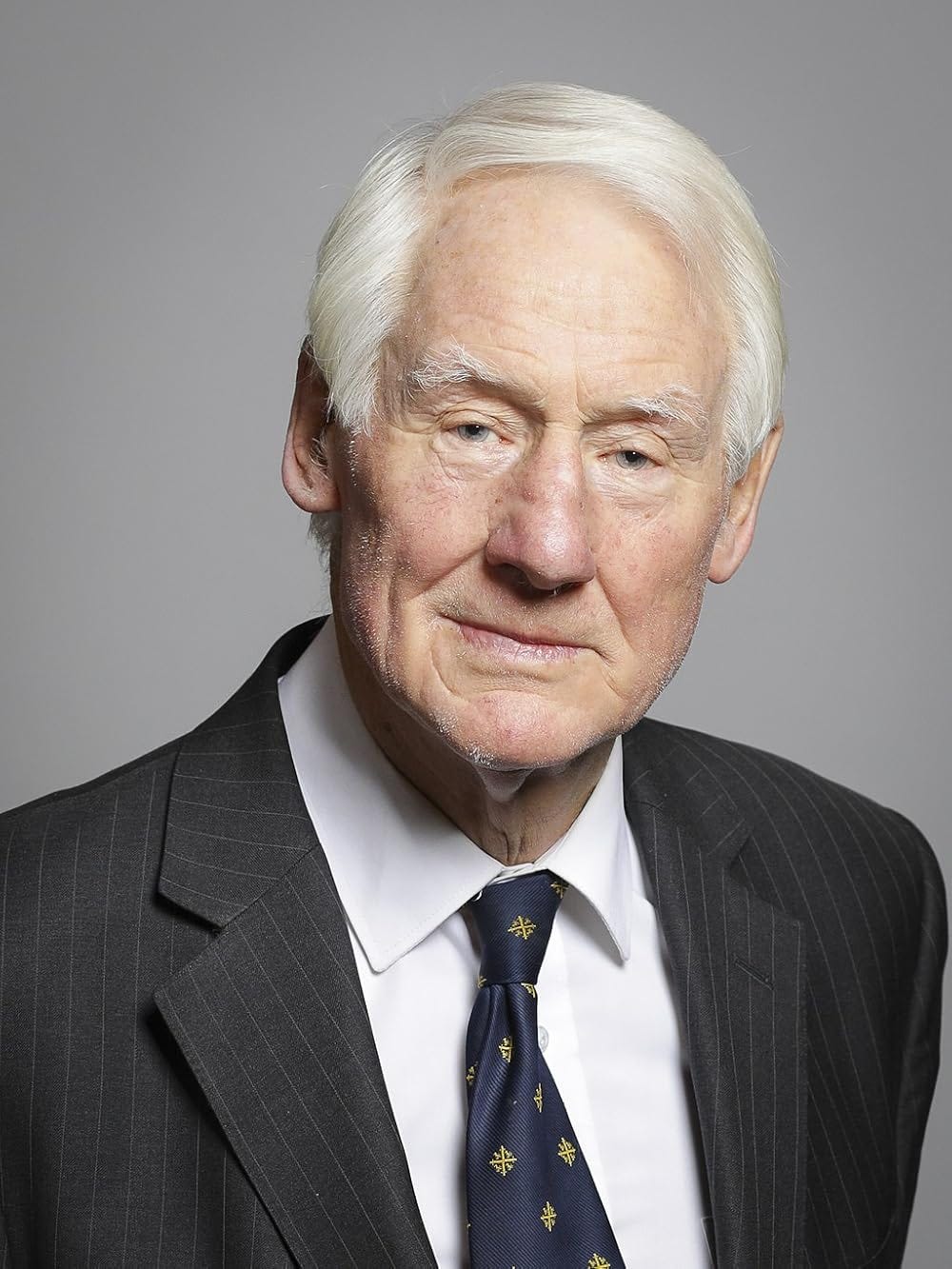

Robin Butler’s contribution to British public life is monumental. As a former Cabinet Secretary, his years of service epitomised the ideals of impartiality, discretion, and quiet competence that the Civil Service holds dear. His wisdom has been a guiding force in turbulent times, and his ability to rise above the political fray has won him admiration across the political spectrum. Yet, his recent intervention in the House of Lords debate on Civil Service politicisation, though delivered with customary eloquence, was misjudged.

Butler’s argument was rooted in his deep concern for the integrity of the Civil Service. He warned against the growing number of political appointees in senior roles, suggesting that this trend risks undermining the impartiality and neutrality that have long been the bedrock of the institution. His plea was heartfelt and his dedication to the principles of good governance undeniable. However, as two of the “Big M’s” - Lord Mandelson and Lord Maude pointed out, Butler’s case lacked the deep institutional analysis required to grapple with the realities of the modern state.

Lord Mandelson, always able to see the big picture, delivered a put-down so precise it was surgical. He acknowledged Butler’s concern but argued that even the most noble traditions, if left unexamined, can ossify into dogma. Mandelson’s critique was that Butler’s idealisation of the Civil Service painted an incomplete picture. In today’s complex policy landscape, he argued, there are circumstances in which the injection of outside expertise, even of a political hue, can sharpen the tools of government rather than dull them. His words were a reminder that no institution, however venerable, is immune to the need for evolution.

Lord Maude, meanwhile, brought his trademark practicality to the discussion. Having spearheaded significant Civil Service reforms during his tenure, Maude’s perspective was grounded in hard-won experience. In the debate, he referenced his influential paper on Civil Service reform, which highlighted systemic inefficiencies and the need for a more adaptable workforce.

The Civil Service cannot afford to be a museum piece, was how I interpreted his impressive contribution. To meet the demands of modern governance, it must embrace change, including the judicious use of political appointees. His critique of Butler’s position was clear: while impartiality is crucial, it should not become a straitjacket to an elected government seeking change.

To fully appreciate Maude’s argument, you must examine his recent review of governance and accountability. This comprehensive document lays out a roadmap for reform, addressing issues like the need for stronger accountability, a more agile workforce, and a closer alignment between the Civil Service and the priorities of elected governments.

The debate also highlighted a broader issue: the tension between tradition and innovation in public institutions. Butler’s vision of the Civil Service is one of continuity and stability, values that are undeniably important. Yet, Mandelson and Maude’s interventions underscored the risks of clinging too tightly to the past. The modern state operates in a world of rapid change, where policy challenges often require expertise that traditional Civil Service structures cannot always provide, particularly in the regulatory space. The integration of political appointees, when done thoughtfully, can serve as a bridge between policy ambition and effective implementation.

This is not to dismiss Butler’s concerns out of hand. The impartiality of the Civil Service is one of its greatest strengths, and any reform that undermines this risks eroding public trust. However, as Lord Mandelson noted, impartiality should not be mistaken for inflexibility. The challenge lies in striking a balance: preserving the core principles of the Civil Service while ensuring it is equipped to meet the demands of the 21st century.

Ultimately, this debate is about more than the Civil Service. It is a microcosm of a broader question facing many institutions: how to honour tradition without becoming its prisoner. Butler’s legacy as a guardian of Civil Service values is secure, but his argument in this debate serves as a cautionary tale about the dangers of romanticising the past. In contrast, Mandelson and Maude’s contributions point to a path forward, one that combines respect for tradition with a commitment to innovation.

This evolution need not come at the expense of its impartiality, but it does require a willingness to embrace new ideas and approaches. Butler’s voice, steeped in wisdom and experience, will always be a vital part of this conversation. But as Mandelson and Maude demonstrated, the future belongs to those who are not afraid to challenge convention in the pursuit of better governance.

In my opinion, our political system, in particular Civil Service, are in a near-crisis. I am very surprised that this debate did not pick up more media attention, particularly because of Butler’s singling out of Morgan McSweeny. I think for Robin Butler to make the case that it’s the fault of political appointees subverting the system is anachronistic.

If Keir Starmer wants to deliver on his missions, he will do well to encourage our new Cabinet Secretary, Sir Chris Wormald, to work with both parties to implement many of the reforms in Francis Maude’s excellent paper. For that, we should be grateful to all who took part in this debate, and to Robin Butler, whose passion for the Civil Service remains an inspiration, even when his arguments occasionally miss the mark.